Privilege Edition

Unpacking but-we're-so-blessed-so-I-can't-complain.

How many of you have ever been in a conversation with a friend, parent or not, when one or both of you says something along the lines of, “But we’re soooo privileged, so I shouldn’t complain…” I’m guessing everyone. I’m guessing some of you said it yesterday. I am pretty sure I texted it this morning.

It goes something like this:

You, on a doggy walk with a friend: Gosh, I’m really starting to feel the cost of groceries! Since when did oat milk need its own line item in the budget?!

Friend: I know, right?! Forget refilling the pepper grinder. No more pepper for us.

You: But I really shouldn’t complain because we have two incomes and help from my in-laws and we are soooo lucky.

[two minutes pass and conversation evolves to be about division of labour around Thanksgiving dinner]

Friend: …and he has NO IDEA how much goes into the planning, and the shopping…

You: Oh totally. No idea! That’s so hard.

Friend: But really, he’s lovely, he works so hard, he’s so good with the kids, so I shouldn’t complain…

You: Of course, yeah! He’s great!

Complaint among relatively privileged people who go on to apologize for their complaint: many people did this in interviews. In response to a question about the family routine or pressure points, a participant would offer a complaint or critique, followed by an expression or gratitude or recognition of their privilege.

What are we doing when we wrap our complaint in a bow of gratitude? Have people always talked this way, or is this self-consciousness a new social tick? Is this kind of comment racialized or gendered in particular ways? Let’s talk about where complaint goes when it stays on the inside of people and/or is released politely in these conversations between friends. First, more about who responded to the survey.

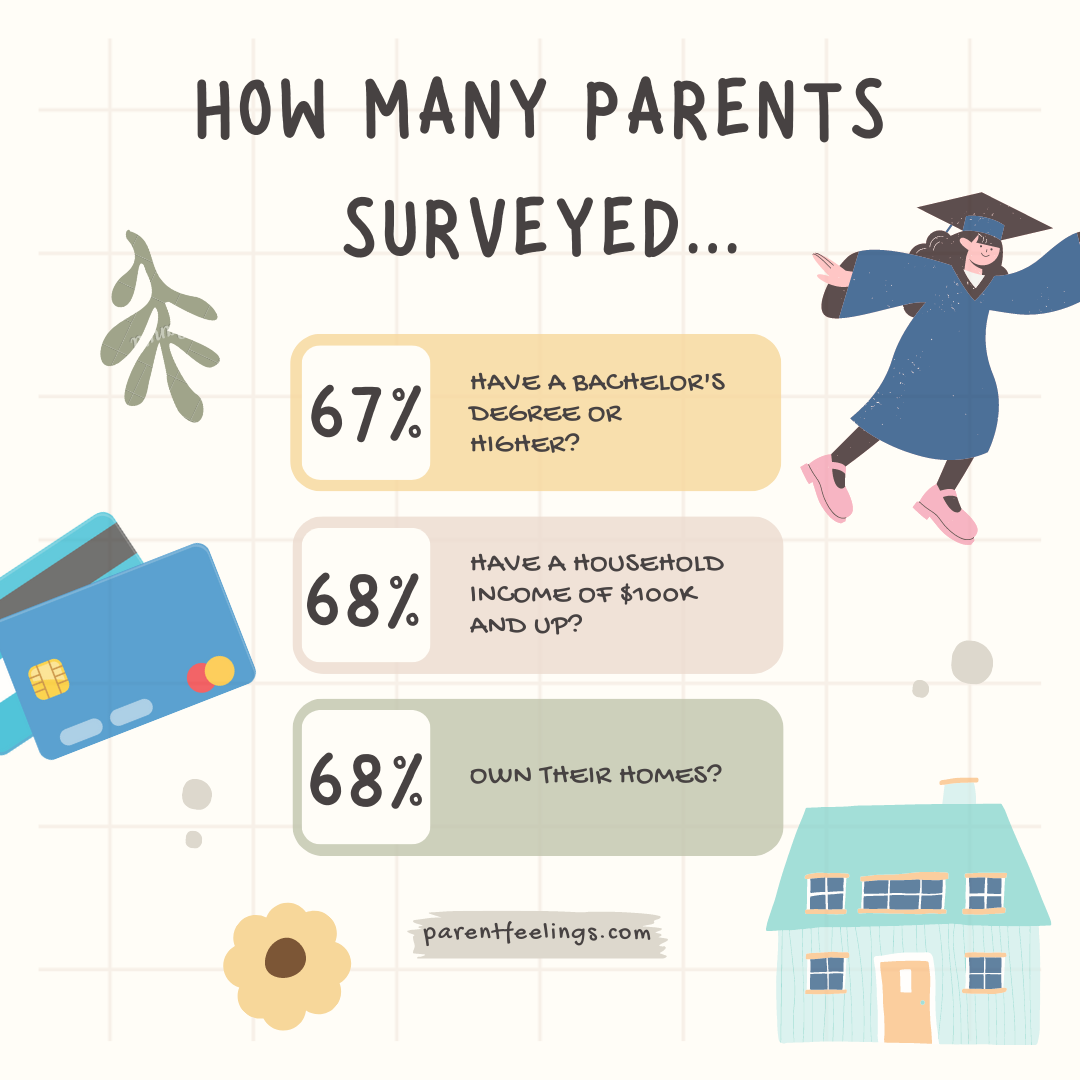

When surveyed…

As this graphic suggests, most respondents were college-educated, most were home owners, and most earned household incomes above the median in Canada (the median household income of couple families with two children in Canada is around $145K). Approximately two thirds (64%) of respondents make between $100K and $300K annually before tax (note: a few respondents who are closer to the $100K-mark commented that this feels like a big range and that earning an extra $100K would make a big difference). Roughly one third (32%) of respondents reported having an annual income between $100K and $150K, while another third (32%) reported having an annual income between $150K and $300K. About 15% of respondents reported having an annual income between $75K and $99K. This distribution might suggest that the sample population surveyed has a slightly higher median family income than the general population.

Complaint

One of the most beloved and energizing scholars and public intellectuals of our time, Sara Ahmed, studied what happens when people make complaints, formal and informal, in institutions like universities. Her book Complaint! (2021) is an extension of her lifelong work on being a feminist killjoy—being willing to kill the joy in the room by not laughing or going along with the group because you don’t agree with the harm being promoted by the person or people taking up space.

In Complaint!, Ahmed details the ways in which complaints come to stick to the people making them. Complaints interrupt the flow of things. Someone has to deal with complaints. If a student complains that a professor repeatedly uses sexual innuendo during lab, the person receiving the complaint has to respond in some way, typically according to the guidelines of a complaint policy. The complainer is therefore disruptive, making work, making things awkward. Nobody wants to be seen as a complainer.

This makes me want to make more space for my kid to complain to me. Just not about dinner. Can Dr. Becky tackle this?

Recognizing Privilege

Sara Ahmed is talking about people with less power complaining to powerful institutions and those who agree to maintain their norms. We all have at least a foot in one institution or another. We know what this looks like and how it feels to be on the wrong side of a complaint.

Several interviewees, particularly those in two-income couple families, were quick to address their positions of relative privilege when it came to complaining. Whether due to income, generational wealth that grants access to home ownership in Metro Vancouver, race, family help with childcare, or an awareness that these are connected systemically, the parents we spoke to were typically reflective and conscious of the fact that family life looks different in different households. This finding seems important. Parents have a lot going on. They report feeling like they are on a hamster wheel. And yet, they are aware when they are having a gentler time due to their relative access to power.

See:

But I recognize it's from a place of privilege. Because if a lot of my friends are working parents, two working parents, and they don't get home till five or six o'clock and so their kids don't have the same opportunities that my kids have.

And:

But … I also have a lot of privilege in terms of economic resources of my family, like in terms of white privilege in terms of like being a second generation academic, that privilege of knowing these systems.

And:

We're very fortunate, for sure. No bragging about it. But we're not…we don't stress about money.

And:

Then [the stress of] trying to get the dinner stuff ready…We're lucky we live in a very walkable city. It's very easy for us to get groceries.

And:

It’s hard, for sure, like... I feel burnt out most of the time. But I shouldn’t complain because we are lucky to have my in-laws living downstairs and helping with pickup and drop-off.

And some interviewees pointed out that many are not in a place of recognizing privilege:

I think lots of grown white people have no idea or are not even aware of the small advantages, like the internship and the name on their job application, and all of these ways that their privilege operates. The optimism is that I have so much more resource to teach [my child], and I hope that he's this anti-racist feminist human.

As a researcher, I was struck by how consistently parents mentioned their privilege following a complaint. I am now curious to know what we are doing with these statements of recognition and what we might be able to do without them. What are the politics of parental gratitude?

What else are we doing when we complain about something legitimate—the rising cost of living, unequal labour distributions, the stress of running a household, the challenge of getting kids out the door in time for school—only to quickly call attention to our privilege or luck in this moment? Are we stifling the potential of this complaint when perhaps it needs to hang in the air a little longer? Are we so afraid of coming off as insensitive in the context of widespread inequality that we are willing, ironically, to go with the flow rather than raise our voice to complain; to risk becoming seen as a complainer; to risk complaint being stuck to us?

Audre Lorde, in a keynote address back in 1980, argued that when white women don’t find an outlet for the anger and resentment they are experiencing due to their exploitation by patriarchal systems and relationships, they take this anger out on Black women. She believed in community expressions of rage so that our anger is joined together against oppression.

I wonder what is happening in the politics of parenting now that so many parents seem to be addressing their race and class privilege in casual conversation. Is gratitude putting things in perspective such that some are not experiencing resentment? Is resentment being swallowed? Does this matter for building community?

Research by Matlock and DiAngelo (2015) found that recognition of privilege among parents and action are two different things. When their participants discussed how they apply principles of antiracist parenting to their White children, the main difference between White parents who identified as anti-racist and non-antiracist-identifying parents was awareness. They found minimal modelling of anti-racist action. When it came to school choice and neighbourhoods, parents did what was best to secure the privilege of their own kids. A familiar story, and a relatable one too. More from that study:

“Of 20 participants, 11 (55%) mentioned the use of books when trying to instill antiracism values”

“(65%) interviewed mentioned that school choice was directly influenced by their antiracism values” (74)

“(35%) mentioned talking about skin color as a way they implemented antiracism in their children’s lives” (75)

“Six of the 20 participants (30%) mentioned engaging in antiracism within their children’s schools” (76)

Where to?

As a white parent myself, and one who teaches university students the scholarship and literature on our intersectional relationships to power, I am accustomed to navigating expressions of privilege. We teach students in sociology how important it is to be aware of these things when ethically engaging with the world. I am familiar with listing the many privileges I carry, and parenting only brings these into sharper focus.

The other day, my daughter asked what is the skin colour of people who clean houses. Dread and shame struck, but feminist theory instructs us that indulging these feelings is not useful. Her question is evidence that we can explain as much as we like, but young kids are observing, and everything we do and do not do is political. We can’t help that. We can’t help that we are pressed for time and burnt out, either. But growing from awareness—the gratitude list—to action might be something we can consider, especially in moments when we don’t know what to say.

In Headphones

The podcast Nice White Parents by Serial Productions and the New York Times details the rub between awareness, intentions, and impact. While this podcast is situated in the context of education in the US, many of the political and cultural observations apply. It’s fascinating.

For a short intro, here is creator Chana Joffe-Walt talking about it with NPR’s Terry Gross.

Parent Feelings Book Club

I haven’t read this yet! The Feminist Killjoy Handbook: The Radical Potential of Getting in the Way comes out Oct 3 in Canada. I will get in touch with Massy Books about adding it to our list as soon as it is no longer in pre-order status! I hope it is a reminder to get in the way—risk being killjoys and complainers without guilt and taking fear of stigma in stride—that tired parents, without much time to spare, and in recognition of their privilege, and in the muck of wondering if they are doing the right/wrong thing/enough/too much, might need in their lives.

Do you refuse to laugh at offensive jokes? Have you ever been accused of ruining dinner by pointing out your companion’s sexist comment? Are you often told to stop being so “woke”? If so, you might be a feminist killjoy—and this handbook is for you. In this book, feminist theorist Sara Ahmed shows how killing joy can be a radical world-making project.

Presenting sharp analysis of literature, film, and influential feminist works, and drawing on her own experiences as a queer feminist scholar-activist of color, Ahmed reveals the invaluable lessons of the feminist killjoy, from the importance of asking questions to the power of the eye roll. The Feminist Killjoy Handbook offers an outstretched hand to feminist killjoys everywhere and an essential intellectual guide to the transformative power of getting in the way.

Massy Books is offering discount codes to any Parent Feelings Project recommendation! Please use the code PRNTFEELS for any title recommended here for 10% off. Massy Books is 100% Indigenous owned and operated and a member of the Stó:lō Business Association.

The Parent Feelings Project Newsletter is here to provide brief updates on research findings to our participants as well as links to resources that might be relevant to this community. Please feel free to unsubscribe at any time. Findings will also be posted on the research website. https://parentfeelings.wordpress.com/survey-preliminary-findings/